This sums up everything I have been thinking and reading over the past couple of years. It discusses radical feminism, why we marry later in life or not at all, the reasons why men choose not to marry at all, the conflicts modern women have, and how all of this affects our society.

I like to find the underlying causes of thing. Many people like to deal with the symptoms and not the root cause. If you look back over the years at how we arrived at where we are, you might come to a better understanding of why we act the way we do. Read this piece and you might see male/female relationships differently.

By Suzanne Fields 1999

We often hear from radical feminists about how the world has to change so that women can be more successful and happy, but we hear much less about these matters from conservative women. I think there are several reasons why.

Conservative women have generally been raised on the traditions that have been handed down through the ages which seem as obvious as the Old Wives Tales passed on from generation to generation. Until modern times, giving birth was dangerous for both mother and child. Raising children was treacherous territory. Survival was hard.

Motherhood was a full-time occupation, difficult and demanding. For centuries women did what they had to do to be responsible for their children. Men sometimes took advantage of a woman’s physical vulnerabilities, but except for certain artists and writers along the way, motherhood was rarely scorned by women until the 20th century. Simone de Beauvoir was the great grandmother of contemporary feminism. Her book, Second Sex, was the “classic manifesto of the liberated woman,” published in France in 1949 and in the United States five years later. She dismissed a pregnant woman as little more than an incubator.

A decade later Betty Friedan published The Feminine Mystique, in which she wrote that suburban mothers with college degrees suffered from a disease without a name. Its symptoms were frustration, boredom and a lack of personal identity. Gloria Steinem famously followed with the aphorism that became a mantra of modern feminists: “A woman needs a man like a fish needs a bicycle.” (Years later, in her own 60s, she discovered that fish sometimes do ride bicycles, and took a husband.)

While post-feminism ushered in a backlash to much of this nonsense, radical feminists on elite college campuses, by now the tenured professors, continue to give motherhood a hard time. In “Women’s Studies,” especially, it has not been politically correct for a young woman to say she yearns to be a mother more than a doctor, lawyer or women’s studies professor.

I came of age in a transitional time before women’s studies was even a gleam in the eye of a Ph.D. I’m the mother of three grown children, still married to my high-school sweetheart and I have a Ph.D. in English literature. I’ve been a newspaper columnist since 1984. My personal experience illustrates the complexities of feminism and family that women face today.

My father was a traditional father, a full-time breadwinner, and my mother, who worked before marriage, enjoyed being a full-time mother after my brother was born. I was born five years later. My father liked the role of protector, and my mother took pride in being “Mom,” cooking hearty meals (lots of roast beef and mashed potatoes), knitting beautiful sweaters and afghans. She was a block warden during World War II, scouring our neighborhood to make sure all lights were out during air-raid drills, and when we needed her less as we grew up, she did volunteer work for charities. My father didn’t want my mother to work and my parents felt lucky she didn’t have to.

When I was growing up a husband and wife, father and mother, understood their mutual obligations and responsibilities within the family. The larger culture supported traditional roles. In what seems crucial to me, my mother and father maintained traditional roles and even with the mundane tasks of raising children never lost their sense of romance. I remember my mother and father walking down the street holding hands.

When I was grown my father told me with a catch in his throat, “You know I really don’t think I could have made it without your mom. She was the source of my strength.” He never talked about “bonding” or “sexual attraction” or “relationships,” but it was clear to me that my mother and father remained close even as they grew older and often moved in different directions in the world inside and outside the home. What was important was the way they lovingly played out those differences for my brother and me, as at the family dinner table every night.

During the years that I was growing up, marriage–not divorce–had the edge. Divorce was stigmatized. That held its own set of problems, but it also meant parents tried harder to stay together “because of the children.”

I have a number of friends who were divorced in the 1960s and 1970s and many of them tell me that if “everybody” hadn’t been getting a divorce, they probably wouldn’t have, either. They began to feel that they may have merely exchanged one kind of perceived “unhappiness” for another. (When I tried to play match-maker for one of my divorced friends, I sometimes concluded that the only man I could think of to suit her was her former husband.)

I followed both a traditional and untraditional path in marriage which gives me a rather unusual perspective among many women today. I wasn’t driven toward a career at first, but I always knew I would work. I earned a Ph.D. with three young children in tow. That wasn’t always easy for them or for me or my husband, but it was my choice.

In retrospect, my husband and I both did a lot of growing up in our marriage because we were both only 21 when we married. We did not have children right away, which gave us a few years together before the overwhelming responsibilities of parenthood. Today men and women are marrying later and couples are having children later. The trade-offs are obvious. I know very young grandmothers who are glad they had their children early. Those decisions are very personal ones. The biological clock is a stern reminder that some choices run out.

Today cultural changes determine different choices, for better and for worse. The cultural edge is with career over motherhood. That’s why so many mothers celebrate a day called “Take your daughter to work.” But that’s a superficial idea, at best. No child gets even a hint of what real work is like on one day, any more than someone could get an idea of what motherhood is like by spending only one day at home.

Feminism has ushered in some positive choices for women, but radical feminism has limited others as well. A downside of the sexual revolution that accompanied feminism is the coarsening of male-female relationships. As a result a subculture of men has found it easy to be self-indulgent and irresponsible. It’s from this group of men that I derived my original title: “Men Behaving Badly.” I’m talking about men who do not take their responsibility to women or children seriously. I added women in a parentheses because it became clear to me that women contribute to the problems they confront in men.

Stand-up comic Susan Easton says that one of her friends belongs to a men’s group called, “Single Heterosexual Men Who Harbor No Hostility Toward Women.” Asks Susan: “What is there, one member?”

“Men behaving very badly” was a metaphor in the ’90s (when this essay was written.) It was a striking headline in the New York Times in the summer of 1997, calling attention to an article about one of the nastiest contemporary movies on the theme of courtship, In the Company of Men. It’s about two angry men whose sole purpose is to date a vulnerable young deaf woman, court her, take advantage of her naivete’ and trust, and then to dump her. The operative word is “dump,” a word that became trendy as more men treated more women badly. I had never heard the word when I was in high school or college, but I hear many women using it today: “So he dumped me.”

In a later movie called Your Friends and Neighbors, by the same director, women act as badly as men. Their relationships are gross and the betrayals are prolific. The two movies framed the dark side of romance at the end of the millennium, words set to the sound of the dissonant music of a farcical funeral march: This is how the sexual revolution ends, not with a bang, but with a whine and a whimper. In this scenario many women became equal opportunity sexual aggressors.

These were not great movies, but philosophically and intellectually they provoked. The director said that he personally trusts “traditional values” and makes these movies because he wants men and women to realize what has happened by trashing those values.

Ronald Reagan was ridiculed when he described women as the civilizing influence on men. Cartoonists caricatured him wearing a leopard skin, carrying a club, with his wife Nancy pulling him by the hair. Ridicule or not, his insight was right on. Women were, and are, the civilizing influence. When women gave up that role men began behaving badly and the culture approved. It was not all the fault of their testosterone.

The changing culture and feminism loosened the traditional demands on men even as it freed choices for women. Every revolution brings its own set of compromises and is bound by the iron law of unintended consequences. The feminist revolution and the sexual revolution were powerful revolutions, and changed the way we articulate our desires.

The contemporary feminist revolution in this country began in the middle of the 20th century, a considerable time after we got the vote. Women joined consciousness-raising groups, single-sex gatherings with a single theme: badmouthing men. Women spoke ill of the absent and the absentees were their dates, their steady boyfriends, their husbands and former husbands.

“The sexual revolution,” writes feminist-fatale Camille Paglia, “has removed all kinds of protections from young women that male gallantry once provided.” Women who wanted the pleasures of sexuality without commitment got what they asked for.

Freud said “Anatomy is destiny.” It was a gross oversimplification, but when women decided to ignore the core of truth in Freud’s remark they threw the baby out with bathwater, literally and figuratively. As a result women often lose, big. You could ask any woman who hears that loud ticking of a biological clock, who desperately fears that time is running out on her ability to bear children.

Focus for a moment on the long view from 1950, and the birth of Playboy magazine. The theme of the Playboy philosophy, laid out at such length by Hugh Hefner, was a simple one: let men be boys. It was a magazine dedicated to fun. Real men, according to Playboy, no longer require marriage to affirm their masculinity. They could play at being boys, enjoying the hedonistic lifestyle of the sports car and the stereo and the glamorous figures they found in the whiskey ads in Playboy. They could fantasize about an airbrushed nude with a staple in her belly button. Then they could set out to find a real live nude of their own.

Playboy loved women, hated wives. The magazine made fun of alimony. Hence Barbara Ehrenreich, in The Hearts of Men, argues that the men who came of age through Playboy precipitated the breakdown in family values before modern feminism even came along. Playboy made irresponsibility glamorous, appealing to men who wanted to run away from commitment. What’s bizarre about this happenstance is that twenty years after the first publication ofPlayboy, radical feminists rallied with men in their quest for independence, to the point of telling women that it was demeaning to take alimony, that freedom was worth the price of no-fault divorce.

Between the extremes of Playboy‘s philosophy and radical feminism, women and men stopped looking at courtship, marriage, motherhood, fatherhood, family life and child-raising with the traditional assumptions. It took the backlash of impoverished victims of this change, aging, single, childless women and single-parent families headed by women, to get us to think again.

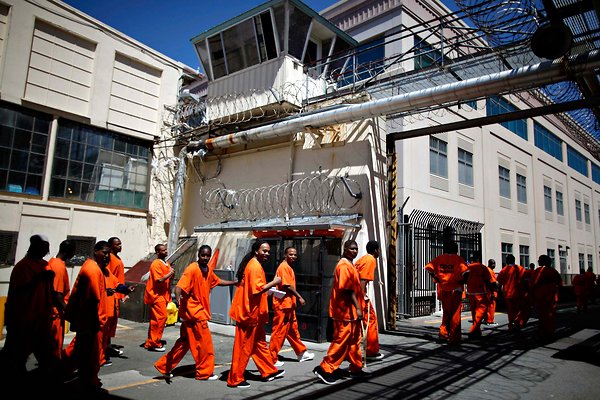

Perhaps the saddest victims of men who behave badly are the fatherless children, abandoned by men. Boys who grow up without a father repeat the cycle because that’s the only model they know. A daughter who grows up without a father is unable to develop trust in that first man in her life, a deep emotional wound for her future expectations of men.

As the dissatisfactions percolated in male-female relationships in the ’70s and ’80s, it was still difficult to speak openly or get respectful media attention paid to these hidden costs of radical feminism. The radical feminist ‘attitude” lingers on college campuses today, and indeed thrives in the faculty lounges.

I visited many college campuses in the ’90s to talk about family and feminism and the ensuing conflicts. Young women who were imbued with the sensibilities of ‘women’s studies’ asked a great deal of hostile questions. They didn’t like full-time motherhood for anybody (unless mother was a man.). For these women a career must come first for every woman. If someone disagreed with that position, she better keep her mouth shut or she would experience the worst kind of stigmatizing.

I often voiced criticism of the one-note women in women’s studies courses, but it was hard for anyone to come to my support. After my speech, however, many women came up to me to say, often in a whisper, “You know, I really agree with what you said, but I could never speak up. I wouldn’t survive long on campus if I did.” When that kind of attitude is pervasive, there is no dialogue, only emotional censorship. I speak and write often about romance, relationships and courtship and I’ve discovered that many young women are totally unprepared to confront the contradictions in their lives, and there’s a craving for a mature dialogue on the subject.

As men saw that certain aspects of feminism played to their advantage, they joined forces in “equal opportunity.” They decided that it was good for their finances for wives to work outside the home. Often both the man and the woman tested their “love” relationship by living together to see if they really wanted to get married. They chose to put off marriage for the sake of their careers. Some day, not today, maybe when little Tiffany and Brandon arrived, Mom could take a break, but only a short one, and then go back to work. The kids could be dropped off at a daycare center.

These attitudes were often mutually decided. But if-a big if–a woman changed her mind after having a baby and decided she didn’t want to go back to work, well, that was not such a good idea. After all, they both depended on her paycheck as much as his. Many women found themselves beyond the point of no return in their relations with men, in their desire for full-time motherhood.

I’ve had women confess to me that they have become like the workaholic fathers they railed against when they were growing up. They may want to enjoy the companionship of men after work, even a little pampering, but there’s a slim chance for that.

Typically, a professional woman will tell me she misses being catered to by a man. She wants her mythical man to get her tickets for the baseball game or the play, ask her which movie she wants to see, to tell her how pretty she is, to send flowers and chocolates on days other than St. Valentine’s Day.

These gestures have disappeared in certain quarters. The first stage of romance is dissipated when sexuality takes over too soon. “Cohabiting” is the big word in the modern courtship vernacular. Cohabiting means living together without the blessing of judge or priest, preacher or rabbi. It also means the “cohabitees” lack the blessings of their families and friends who can lend crucial support to their choice of mate. A number of women say the reason they cohabit is that they don’t want to divorce like their parents did. They think if they get to know the guy better, by living with him as well as sleeping with him before marriage they’ll have a greater chance of marital success. Unfortunately, statistics prove otherwise. Those who cohabit before marriage have higher rates of divorce than those who don’t. Of course many of these couples break up before marrying. It’s easier to walk away when there’s no knot to untie.

I’ve found that many career women are pleased with their professional lives, but find it difficult to turn off their aggressive work personalities and sink into a romantic mode with a man in the evening. The softer side of femininity is harder to get in touch with. Men react in kind. In the high-pressure world in which many of us live, the cell phones, computers and answering machines are a convenience, but make it more difficult to separate work and love.

Most women want what women have always wanted, marriage, motherhood and grandmotherhood. They want to cherish and they want to be cherished. They want to nurture and feel protected. They want to be independent and they want to be cared for. But roles are so complex today that it is very hard for a woman to unify the wishes held in the secret places of the heart. Many women say that they do just fine living the life of a singleton, but their voices have a slight bitterness.

As women and men are marrying later, the panic of not marrying arrives later, too. That can be traumatic for a woman. In the past three decades, according to the Census Bureau, the proportion of 20-to-24 year old American women who haven’t married has doubled from 36 percent to 73 percent. Not so troubling, given that women are less inclined to marry quite that young these days. But the number of unmarried women between 30 and 34 has more than tripled, from 6 percent to 22 percent. That’s considerably more scary, particularly when biological clocks are ticking loudly and men refuse to hear them.

“When a woman postpones marriage and motherhood, she does not end up thinking about love less as she gets older, but more and more,” writes Danielle Crittenden in What Our Mothers Didn’t Tell Us.

Kate Worthie, in Esquire magazine (no less), writes the lament of the “retro-feminist” that reflects personally on the single life. “I live alone,” she writes.”I pay my own bills. I fix my stereo when it breaks down, but sometimes it seems like my independence is in part an elaborately constructed facade that hides a more traditional feminine desire to be protected and to be provided for. The title of her piece was “The Independent Woman and Other Lies.” She wanted men in Esquire to see beneath the veneer. But women must also look harder to see beneath the veneer, too.

“We often have to use feminine wiles to make love and work–work. Leslie Stahl, a reporter on CBS’s Sixty Minutes, writes in her memoirs that working crushes female sexuality. It was an odd point coming from Ms. Stahl, since she used femininity to expand her professional role, getting a better interview, breaking down the defenses of a man resistant to her questions, but not to her charms.

Diane Sawyer, once America’s Miss Junior Miss, does the same thing. When she interviewed me in 1984, on my tour for my book, Like Father, Like Daughter, we talked about the importance of women being able to fuse competency and femininity. She looked at me with wide blue eyes and asked, “But isn’t femininity what women have to leave behind?”

That may have been the public feminist position at the time, but I gave a resounding “No” even then. No one uses her femininity better than Diane Sawyer; more power to her. Fast forward to 2002 to Paula Zahn, the CNN news personality who was outraged when a promotional commercial described her as “sexy.” Anyone who can’t see that she’s sexy, with long shapely legs revealed by high hemlines and artful camera work, is blind or a hypocrite. Her seductive looks may not reduce the seriousness of her questions, but it often disarms the viewer and the person she interviews. The point here is that a lot of women mix femininity and competency to their professional advantage and there’s nothing wrong with that except denying it.

Women must accept their responsibility for letting men behave badly. Bridget Jones’s Diary, the best-selling novel and a hit movie in 2001, tells the story of a 30-something single woman in London who sums up her New Year’s resolutions with a list of the men she must learn not to go out with: “alcoholics, workaholics, commitment phobics, people with girlfriends or wives, misogynists, megalomaniacs, chauvinists, freeloaders, perverts.’ She’s trying to be funny, but the list cuts close to the bone of reality for a lot of single women her age. If a woman can’t keep men from behaving badly, she has to try harder to keep one out of her life. And that’s very, very sad.